The Royal Society for Asian Affairs (RSAA) has a huge collection of historic maps, and Central Asia and the Pamirs are particularly well-represented thanks to the society’s links to the Great Game. Below are a few of the maps which include the Wakhan Corridor. You can find out more about the RSAA’s library and archives here.

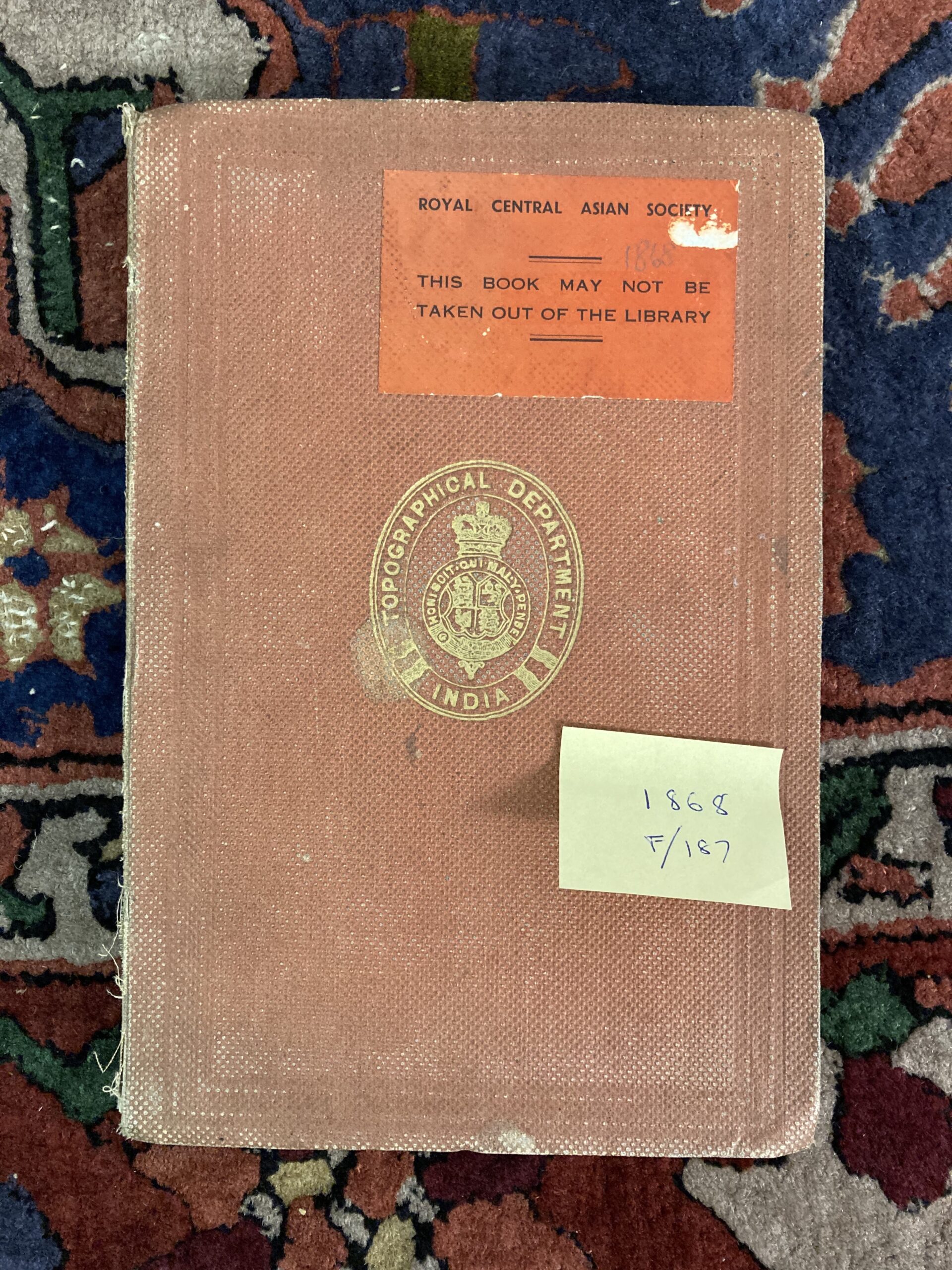

1868: The earliest map of the Wakhan I’ve found so far in the RSAA archives is this one published by the Survey of India in 1868. The map is a hand-coloured photozincograph measuring 39 1/4″ x 54 1/2. The Wakhan Corridor is on sheet #2 in the series.

Of note is that the river is labelled as “Amu Daria Jihoon (Oxus)” and then “Punjah”, spellings which were later standardised as “Amu Darya” and “Panj”. The placing of these names on the map is strange, however, as the Panj doesn’t become the Amu Darya until after its confluence with the Vakhsh, some distance west of Kulyob (Kolab on this map). On this section of the map, therefore, we are only looking at the Panj, not the Amu Darya.

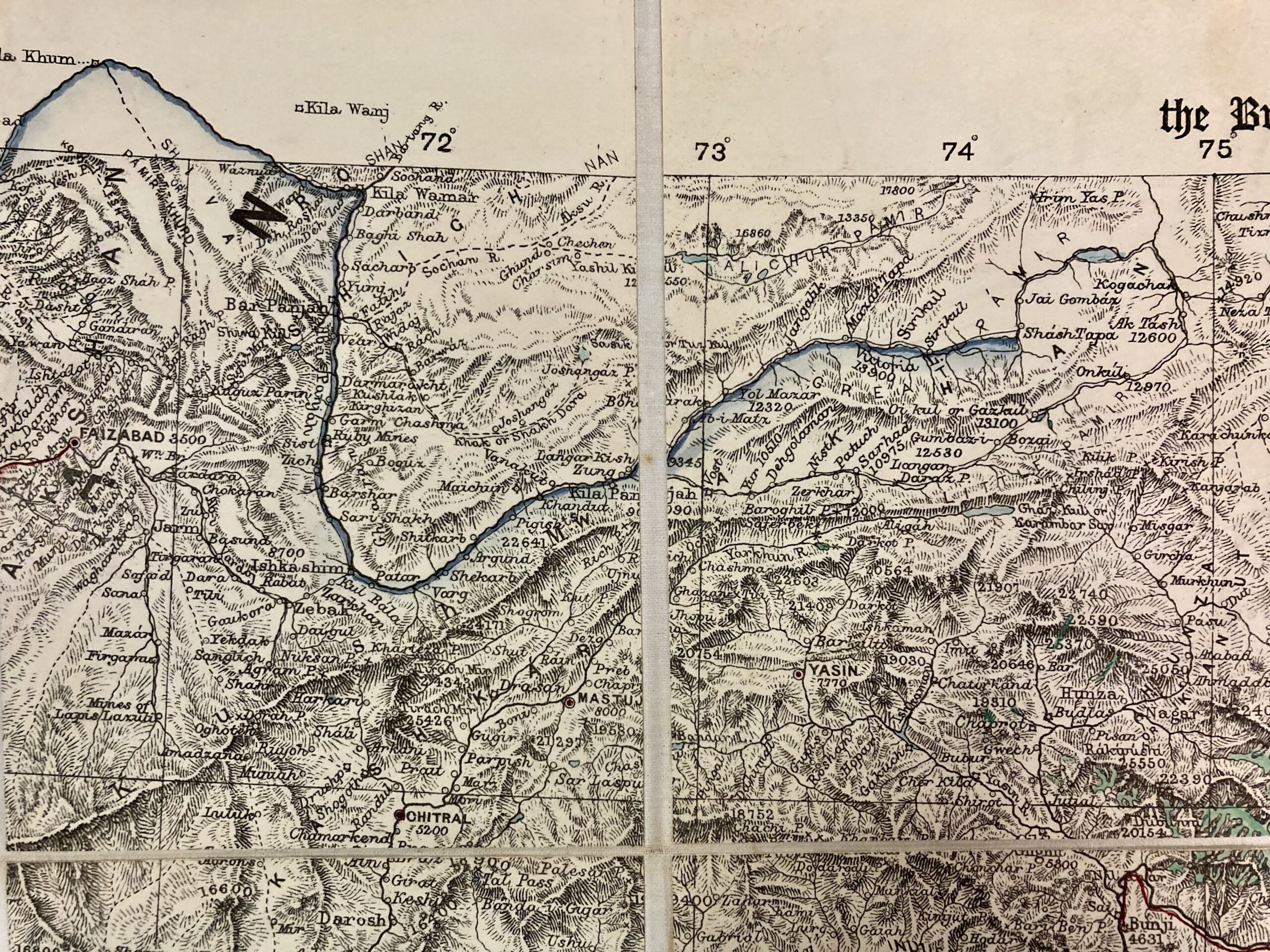

1882: This isn’t a particularly high quality map, but the interesting thing about it is that it previously belonged to Peter Hopkirk (1930-2014), who wrote extensively about the Great Game. I like to think that he used this map when writing The Great Game: On Service in High Asia, Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Treasures of Central Asia, and Setting the East Ablaze: Lenin’s Dreams of an Empire in Asia.

The full name of this map is Turkestan and the Countries Between the British and the Russian Dominions in Asia. It was prepared by James Thomas Walker (Surveyor General of India) and used survey data from both British and Russian officers. The map was published by the Survey of India in four sheets, and the Wakhan Corridor is on the southeast sheet. Unlike the 1868 map, the extent of the Panj is now property labelled.

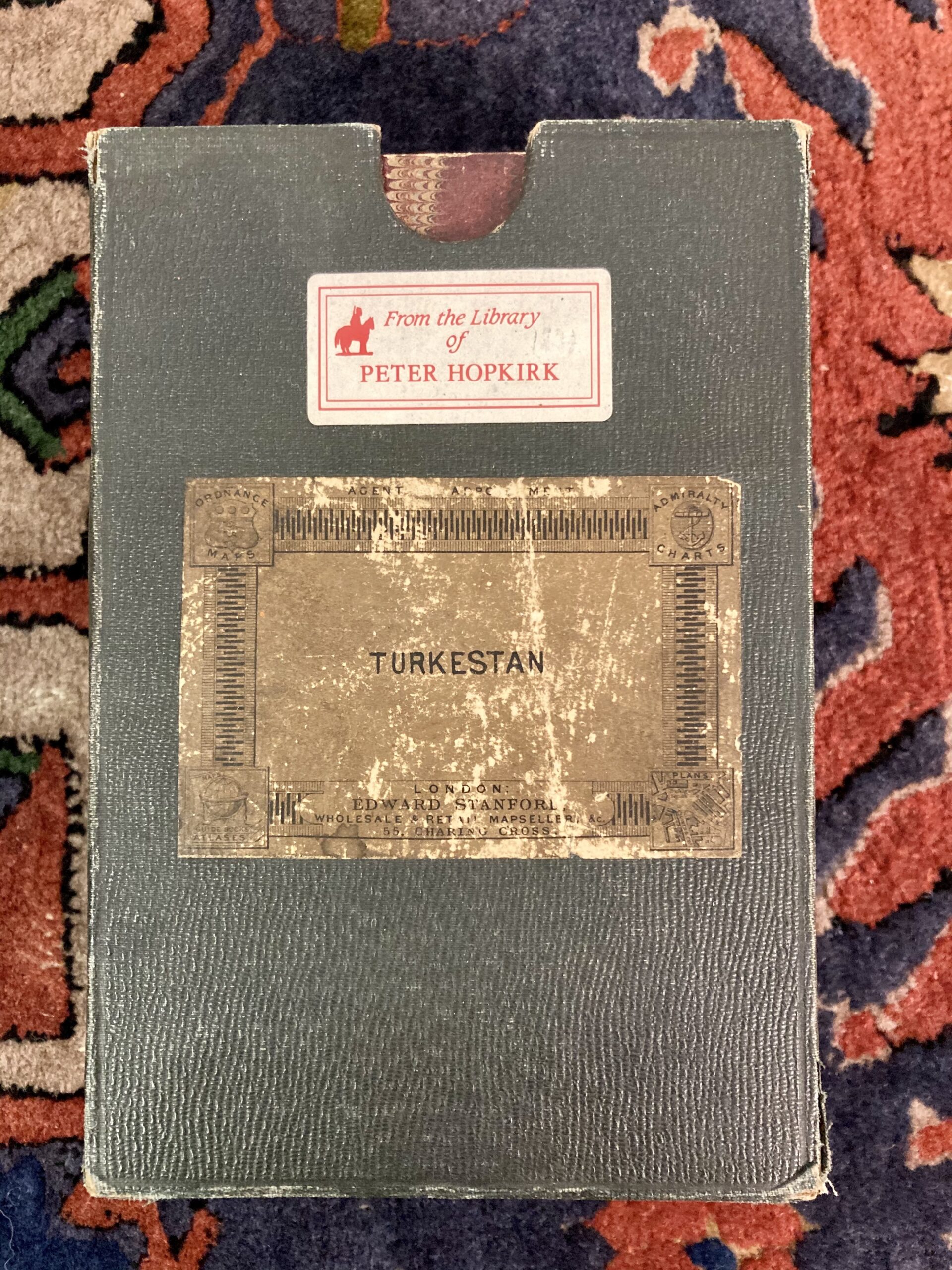

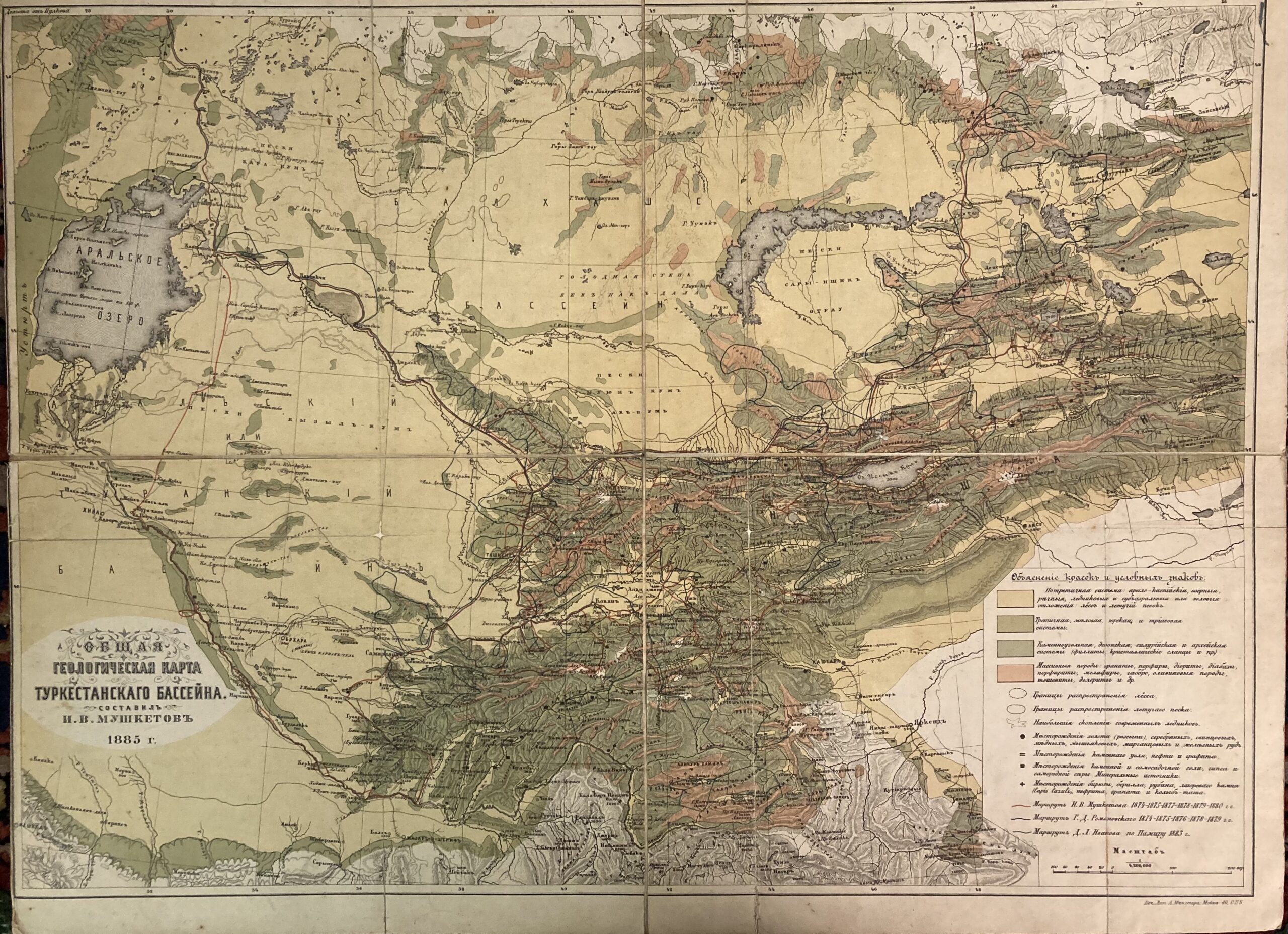

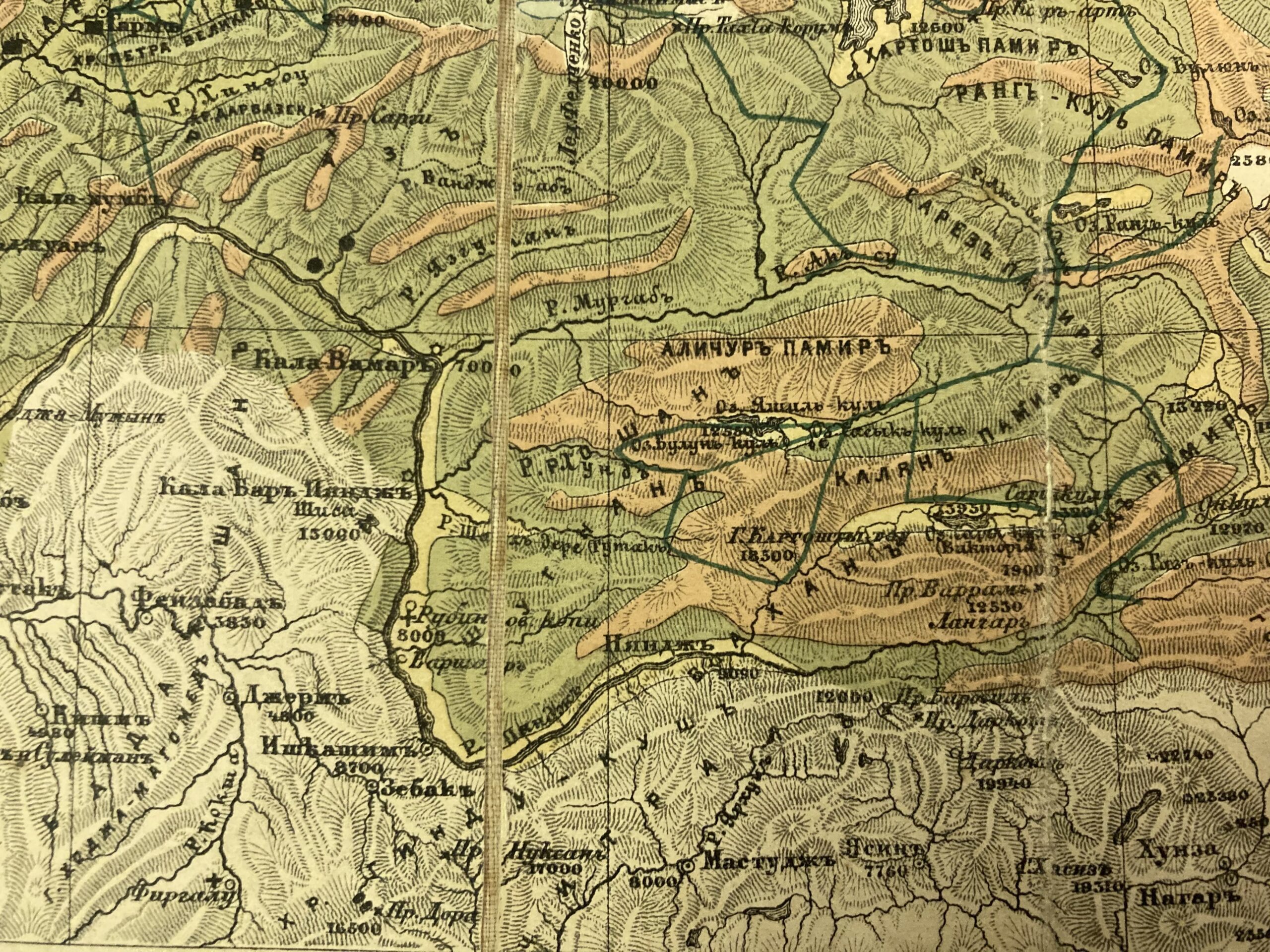

1885: Just as the Survey of India was producing maps for the British market, so too were their imperial counterparts in Russia. This very attractive colour map has a very large scale (1:4,200,00) but does still give some topographical details and shows the main course of the river.

Although this map was published in Russia, like many of the others in the RSAA’s collection it was purchased from Edward Stanford in Covent Garden. You can see the label on the cover. Stanfords, which was established in 1853, still exists and remains one of the best places in the world to buy maps and travel guides.

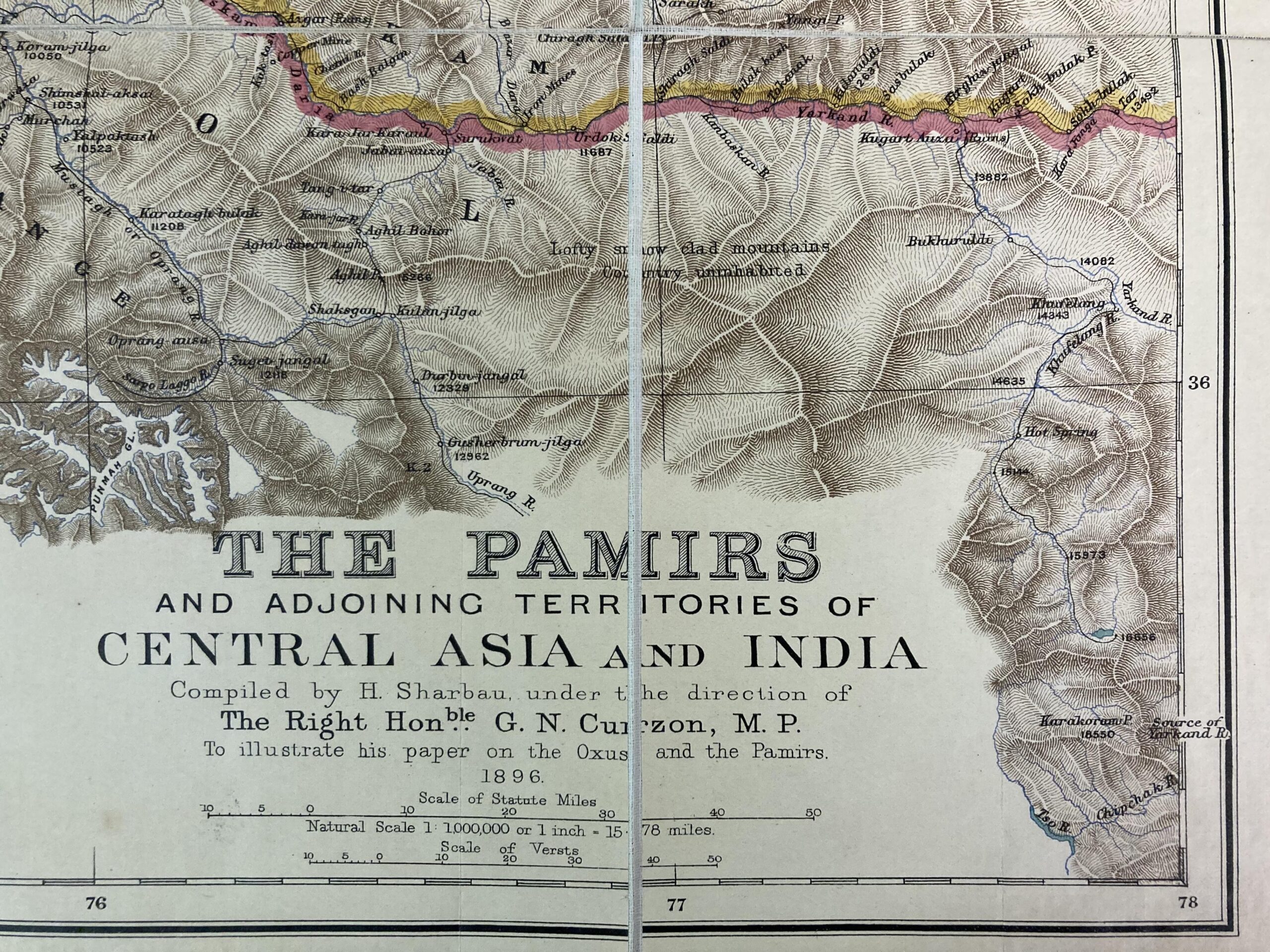

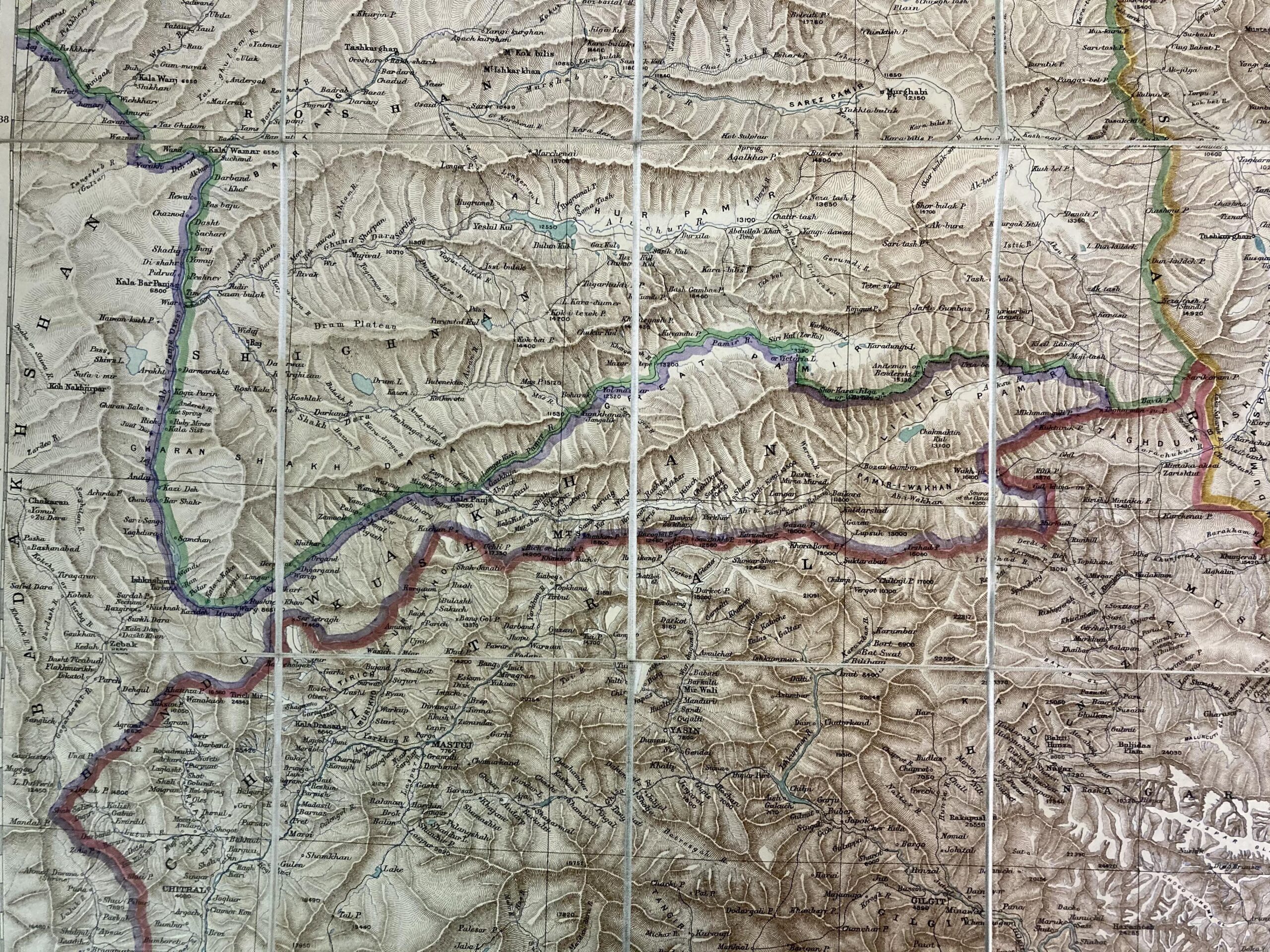

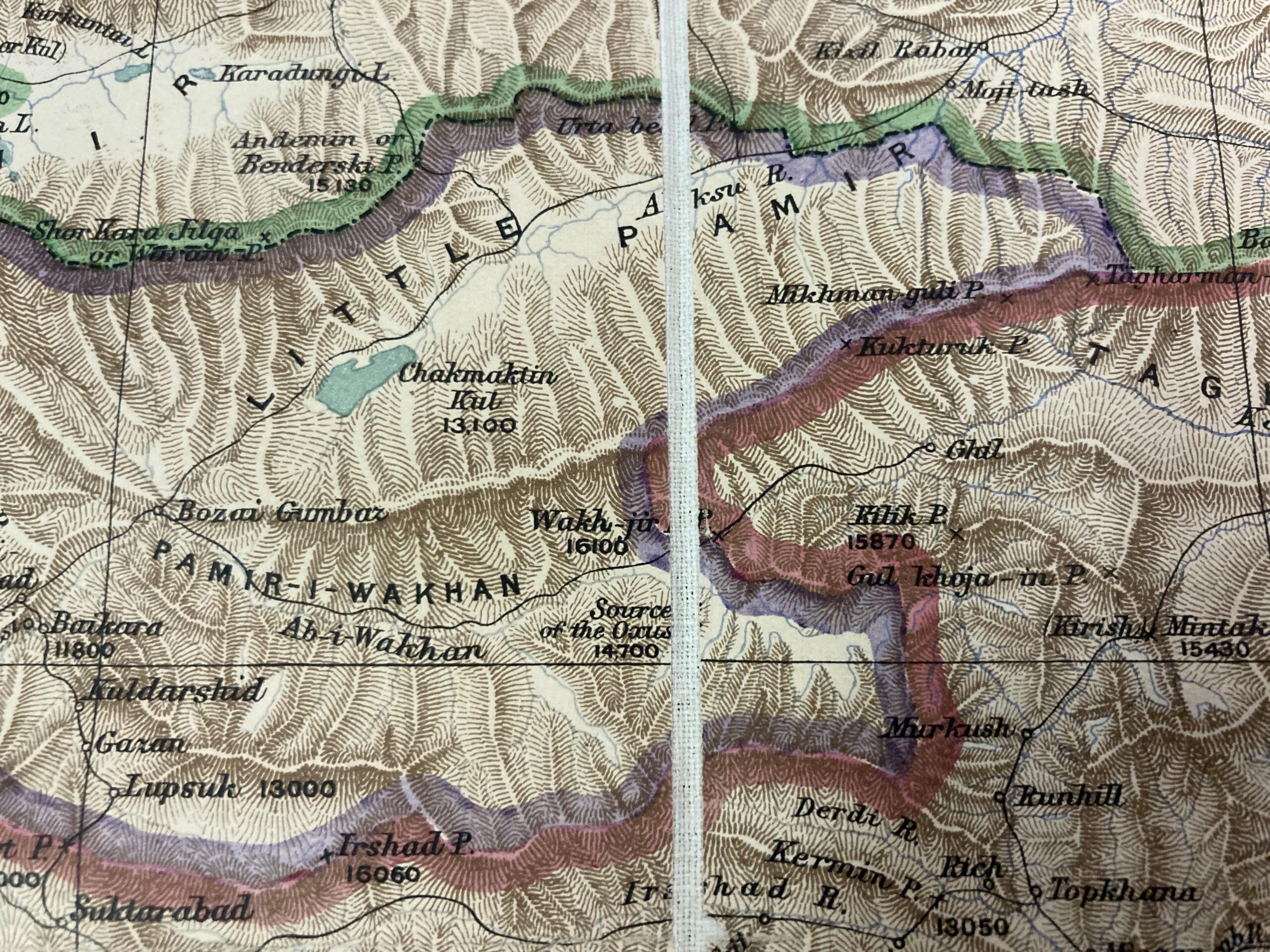

1896: Lord Curzon (later the Viceroy of India) travelled to Afghanistan and the Pamir in 1894, and finding the source of the Oxus was one of his key objectives. He did find a source — the ice cave at the top of the Wakhjir River — and he marks it confidently on this map, which was compiled under his direction and published in 1896. For this discovery, he was awarded a gold medal from the Royal Geographical Society.

This semi-colour map has a 1:100,000,000 scale and is backed on cloth. It measures 24″ x 24 1/2″ and is finely detailed, even showing some of the smaller rivers and settlements in the Wakhan. This map is important because it is the first to identify the Wakhjir as the Oxus’ source, a claim which we expect to disprove during the Oxus Expedition.

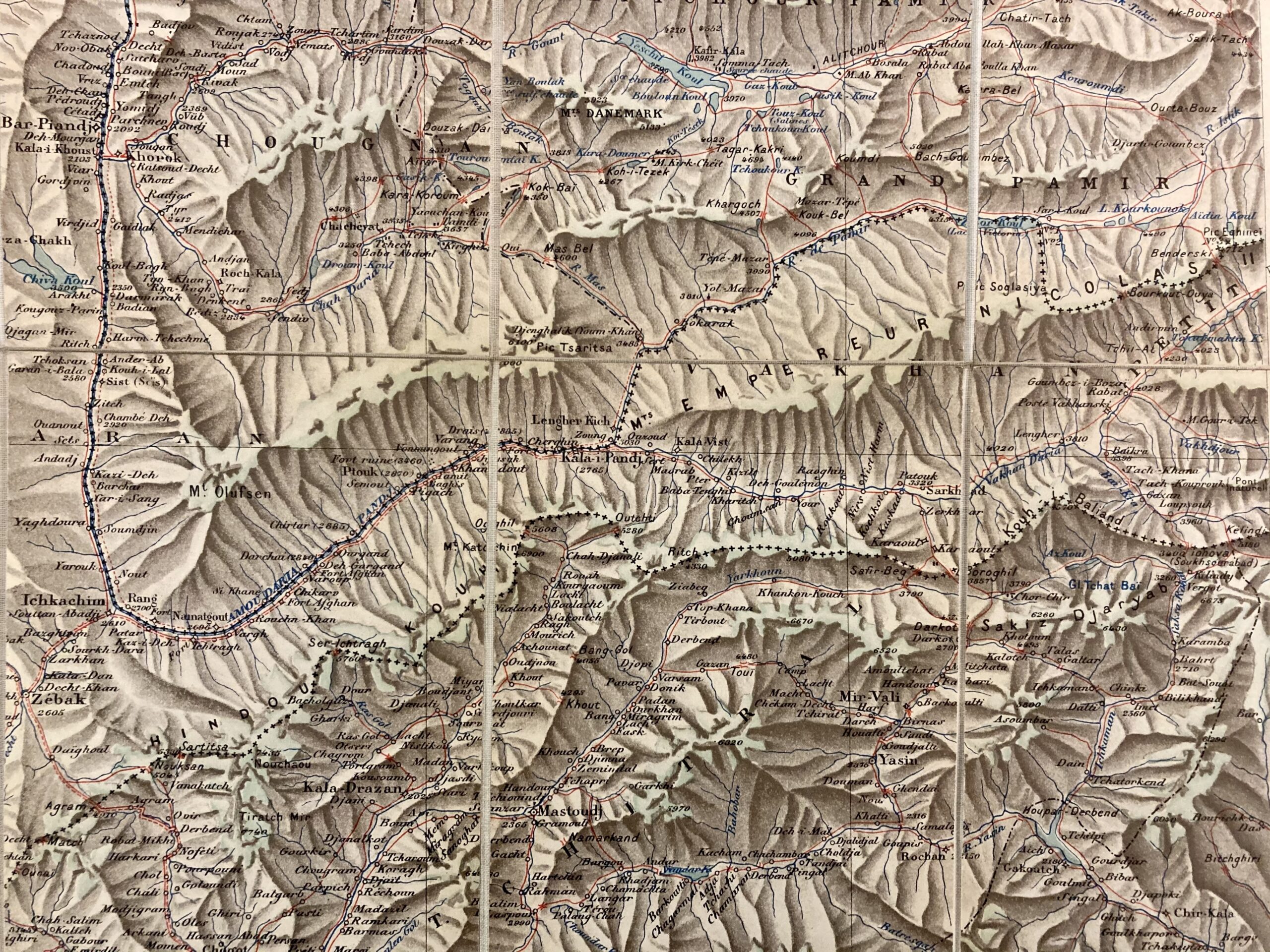

1901: Five years after Curzon’s map of the Pamir was published, France’s Army Geographical Serviced published their own map of the same region in French. It is likely that they used some of Curzon’s survey data, and perhaps also information from Gabriel Bonvalot’s expedition which took place a few years earlier.

The scale of this map (1:1,000,000) is the same as Curzon’s map. Every single village seems to be marked, and great attention has been paid to the naming of places, even if in some cases the spelling is a curious French-Persian hybrid.

This map measures 17 1/2″ x 21 1/2″. It is a semi-coloured heliographic print.

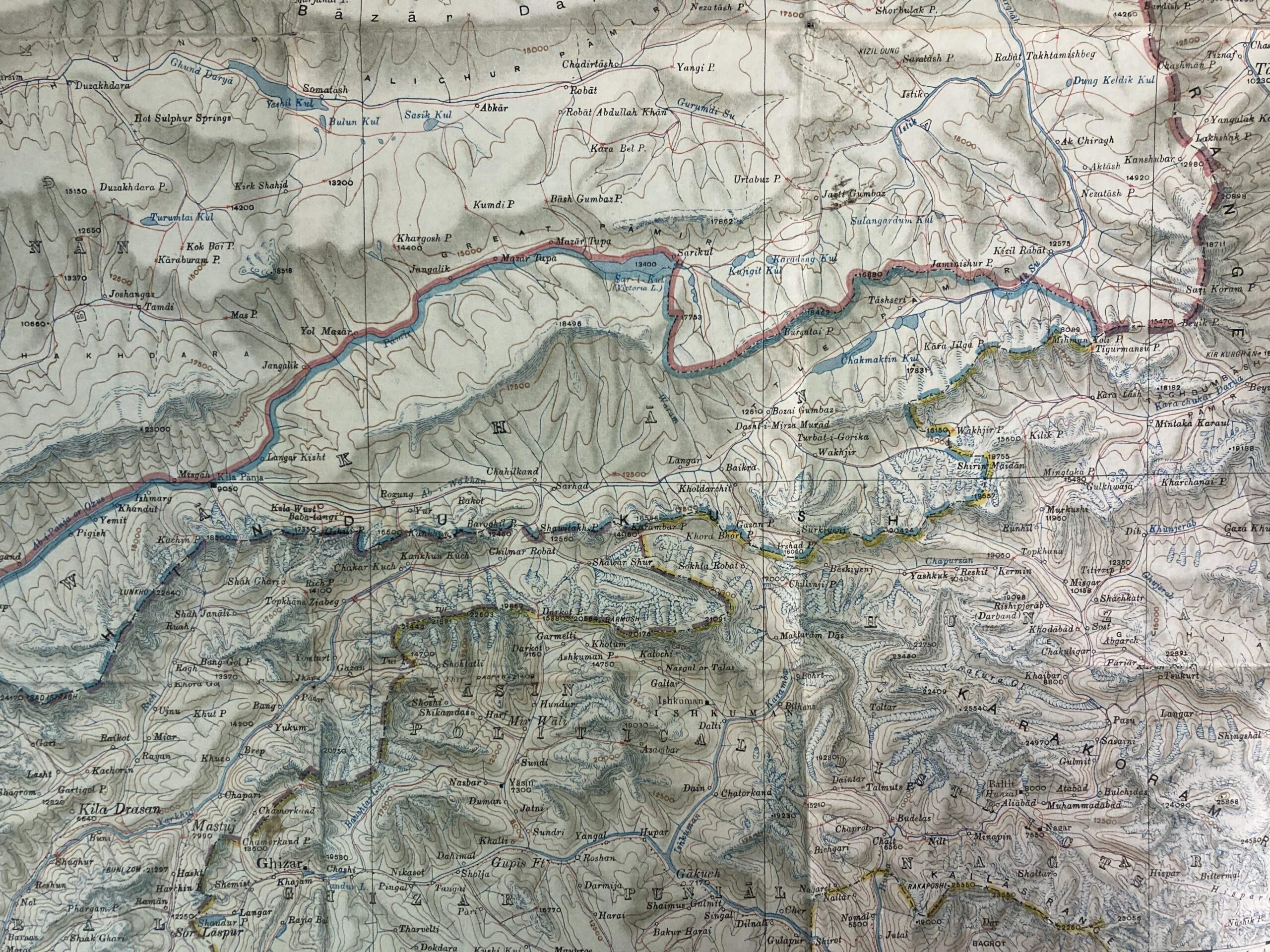

1930: By the 1930s, the Survey of India clearly thought it was about time that they publish another map of the Pamir, incorporating the knowledge obtained from expeditions in the early 20th century. As with previous maps, it has a scale of 1:1000,000 and was printed in semi-colour. This sheet (17 1/2″ x 14 1/4″) was number 12 in the series.

What is clearer on this map than on previous ones, in part because of the colouring, is the size and position of the various water resources. The extent of Lake Chaqmaqtin is much easier to see, for example, as are the huge number of glaciers around Curzon’s ice cave at the top of the Wakhjir Valley. You can see the confluences of the main rivers, too.

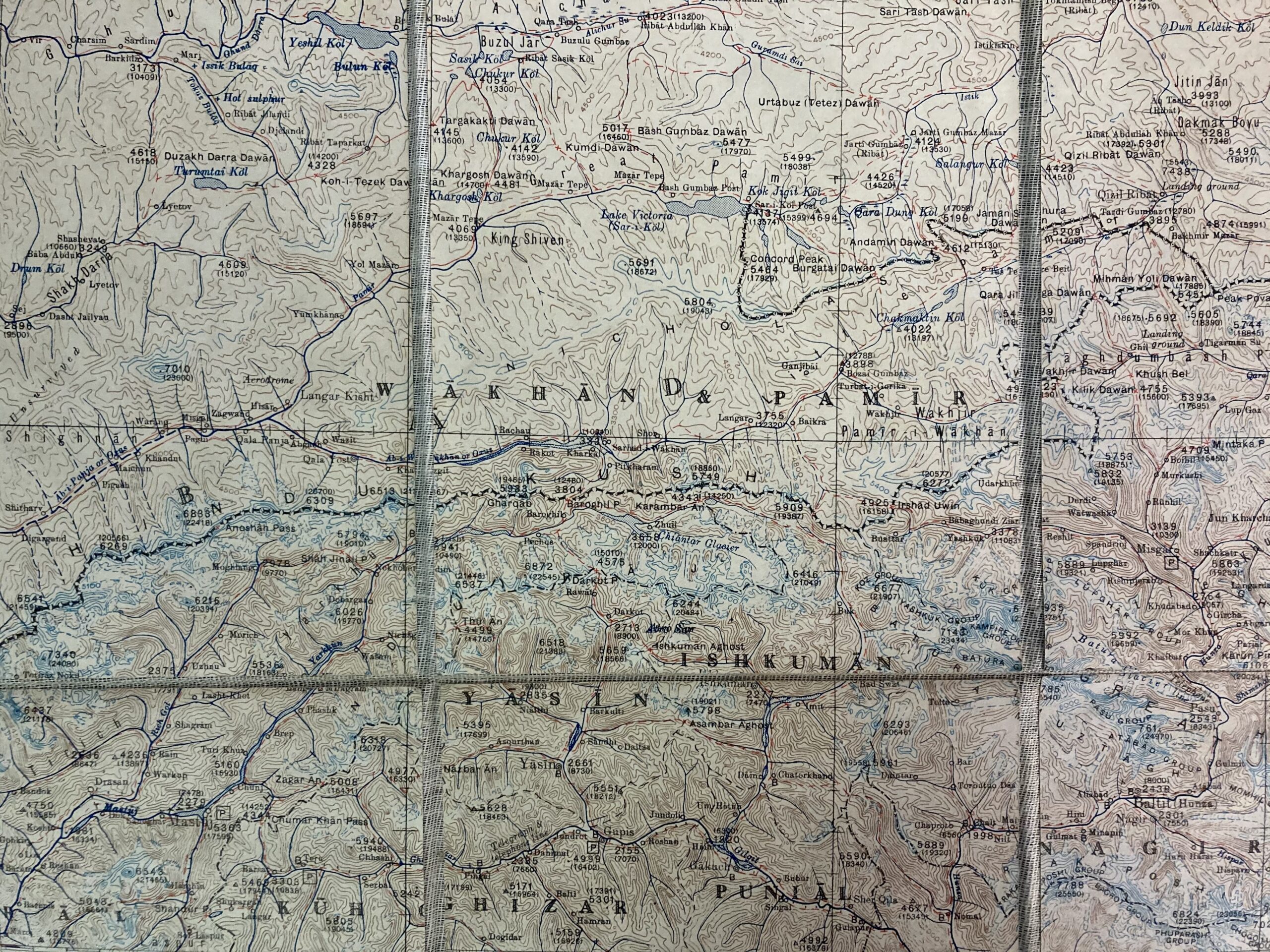

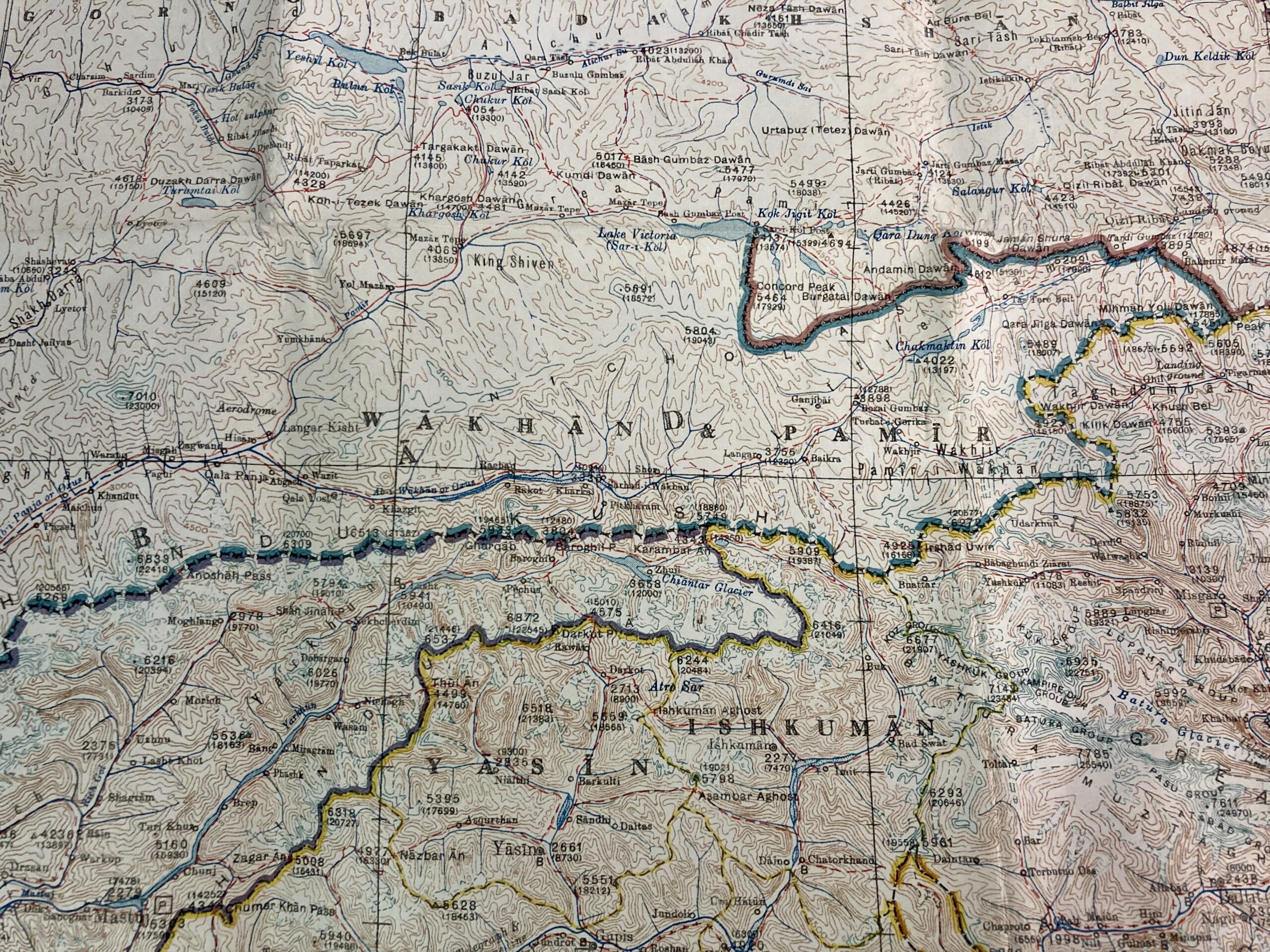

1941: The final Survey of India map of The Pamirs dates from 1941. Priorities shifted during WWII and in 1947 India gained its independence, so surveying and protecting “The Jewel in the Crown” was no longer on the agenda.

Unsurprising for a map made in the dying days of the British Empire, Zorkul is still marked as Lake Victoria. The Wakhan’s southern border with what became Pakistan is well-defined, but there is no demarcation of the corridor’s northern edge.

There are two copies of this map in the RSAA archives, one in better condition than the other. The map is sheet NJ 43 in a series, it measures 17 1/4″ x 21″, and is in semi-colour.

As the archive research aspect of the Oxus Expedition progresses, it is likely that I will find more maps of the Wakhan Corridor and I’ll be glad to share them with you then. I will write a separate blog about modern maps of the area, which in some cases are harder to find and less useful than their historic counterparts!