Afghanistan in early 2021 and Afghanistan in summer 2025 are not the same. Had the Taliban already been in power when we began planning the Oxus Expedition, we might not have pursued our idea of a female expedition from source to sea. But having already committed to it, we wanted to see it through. There are no doubt many well-meaning friends, family, and bystanders who think it was inappropriate to travel in Afghanistan when so many Afghan women are suffering under Taliban repression, that our presence would be used to white-washed Taliban abuse. We therefore wanted to share a few reflections, informed by the women we met and the experiences we had.

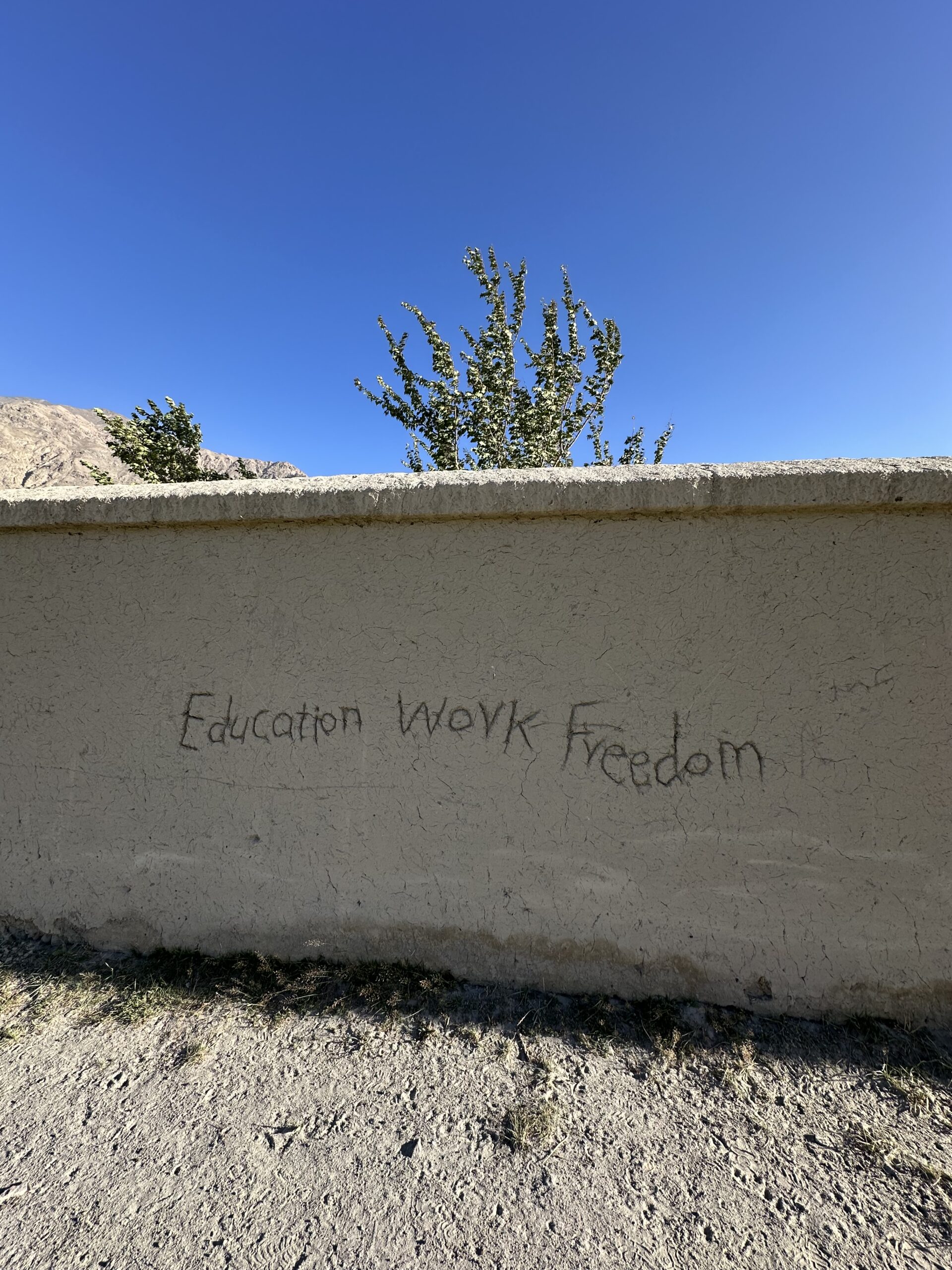

Education. Work. Freedom. These three words were carved in large letters in English and Dari into the outside wall of a family compound in the Wakhan. The women living here had their education stopped short; their brothers continue studying. Determined, they have found ways to keep learning, and to keep teaching, but there’s an anger inside which is turning to sadness and despondency the longer that the Taliban keep girls out of high schools and universities. The world has looked away, leaving these women alone.

A small number of women are still working paid jobs in Afghanistan, but usually behind closed doors. In some cases, these are official jobs, like the woman at the border who physically examines female arrivals to ensure they don’t have anything illicit hidden about their person. More often, women are working in the private sector, for example running a restaurant catering to families in Kunduz. These women are a small minatory, however: many more need and want to be working, to support their families and have financial independence.

If you google the Wakhan Corridor, you’ll see striking portraits of Kyrgyz women and girls in their traditional, vibrant red attire. Road building to the Little Pamir has enabled the Taliban to reach the Kyrgyz communities around Bozai Gumbaz and Chaqmaqtin, and they’ve imported their extreme brand of Sunnism. Young Kyrgyz men have been sent to madrassas in Kunduz and returned radicalised; they now pressure their mothers and sisters to veil their faces or wear a burkha, even though it’s not compatible with the demands of herding livestock. Far fewer Kyrgyz women were visible outside than when I last visited them a decade ago, and most are no longer willing to have their photograph taken.

Foreign women in Afghanistan are treated as a third sex. It is not the only place in the world where this happens, but we acknowledge our privileged position. We were able to enter the women’s quarters of homes, to sit and talk with women in their kitchens and courtyards, and to play with the children. At the same time, we could travel across the country with men who were neither our husbands nor blood relatives. We could wear our own clothes, be visible in public spaces, and continue largely unhindered with our work. We were allowed into the Blue Mosque complex in Mazar-i Sharif. These rights are not afforded to our Afghan sisters.

On our final afternoon in Afghanistan, we visited the tomb of Rabia Balkhi. It is beside the Green Mosque in the ancient city of Balkh, in what is perhaps the only park in Afghanistan where women are still allowed to sit, wander, and enjoy themselves. Rabia is a national heroine because she was the first woman to write poetry in Persian. This was in the 10th century. She was highly educated, independent, and passionate in her love life as well as her creative output. Some say that Rabia is a proto-feminist; but however we define her, 1,000 years after her death, we are still reading her poetry and women in Afghanistan and beyond its borders still find inspiration and hope in her story.

With financial support from Maximum Exposure, we will be helping some women we met during the Oxus Expedition access educational opportunities online and in universities outside Afghanistan. This includes using our network to arrange admissions, visas, and scholarships. The details of this will remain confidential to protect the individuals involved and their families, but if you would like to help, please get in touch.