The source that wasn’t

The Chelab Valley runs from the Nikolai Range on the northern side of the Wakhan Corridor into the plain on the western side of Chaqmaqtin. It is important because its main stream bifurcates at the mouth of the valley, principally flowing into the lake but with a small amount of water also feeding the Little Pamir.

The most commonly used definitions of a river’s source are the stream which begins furthest from the sea; and the stream which begins at highest altitude. A third definition refers to the volume of water that the stream contributes to the river system, and so in the Chelab we wanted to examine the four sub-streams (A-D) which come together, and to establish which of those was the principle.

There are plenty of ways to calculate the volume of water in a stream, but we needed something which was simple to use, affordable, reliable, and wouldn’t cause consternation amongst customs officials or anyone else searching our baggage. In summer 2024 we’d trialled the trans velocity head rod (TVHR) in the UK and found it worked well in test conditions. But a quiet chalk stream running through Wilton is not the same thing as a glacial mountain stream. How would it fare? We’re delighted to say, it worked well.

Glacial streams vary significantly in volume over the course of a day, as the warmth of the sun melts the ice, increasing the water flow. For this reason, we needed to undertake the stream gauging at approximately the same time for each river, conducting the work over several days to allow for the time required to walk or ride between the measuring sites. Working earlier in the day, when the water volume was lower, would also be safer, so we took all the measurements between 09.00 and 10.30.

To start the process, we stretched a tape measure across each stream, from the left bank to the right. Sophie was in the water, wearing waders; and Mahmud Omar gamely kept the other end of the measuring tape in place. This gave us this width of the stream and meant we could easily see where each vertical measurement point — 20 cm apart — would be.

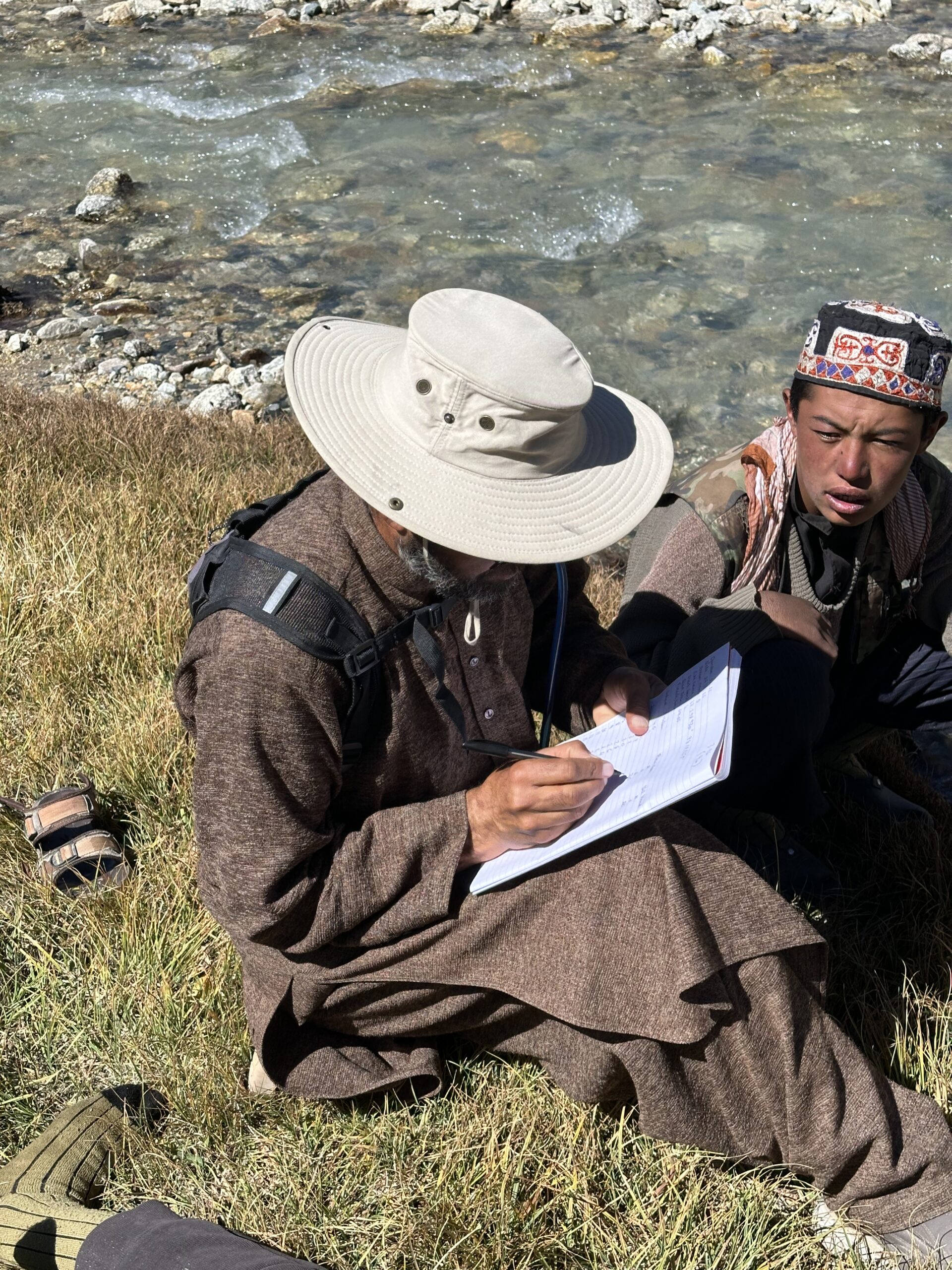

The TVHR is essentially a metre-long ruler made of perspex. You place it in the water vertically, side on to the flow, and raise the end of the clear gauge to the water’s surface to read the depth in centimetres. Then, you rotate the rod 90 degrees so the force of the water pushes against its flat side: there is a clear difference now between the water level on the upstream and downstream side of the rod. You slide the red gauge up to match the upstream water level, and then read off the velocity head in millimetres. Our guide, Salahuddin Esmaeli, recorded the data in a table, and we repeated the process again and again across each stream’s width, collecting all the information required to calculate the cross-section of the stream and the volume of water flowing through it.

TVHR’s inventors, INRAE, provide a spreadsheet for the calculations. Without electricity in the Chelab Valley and not wanting to risk a laptop in the harsh environment, we inputted the data later. These are the results for the four streams

A = 0.535 cumecs (535 litres/sec)

B = 0.136 cumecs (136 litres/sec)

C = 0.114 cumecs (114 litres/sec)

D = 0.490 cumecs (490 litres/sec)

Individually, A is the largest of the four streams which together comprise the Chelab. However, the other three streams have already merged upstream, so the confluence is not of A and D, but of A and the by now larger B-D stream, as the latter already holds the total volume of three streams’ flow within its course. As the mainstem of a river is the larger (by volume) of the two tributaries joining at a confluence, the mainstem of the Chelab is as follows:

A / B-D confluence: mainstem = B-D

B / C-D confluence: mainstem = C-D

C / D confluence: mainstem = D.

We first contacted Jack Wolfskin’s marketing team when the idea for the Oxus Expedition was in its infancy. Little did they (or we) know that it would take four and a half years — not the anticipated six months — to complete the expedition and have results, photos, and videos to show for it. Their generosity and patience are very much appreciated.

We first contacted Jack Wolfskin’s marketing team when the idea for the Oxus Expedition was in its infancy. Little did they (or we) know that it would take four and a half years — not the anticipated six months — to complete the expedition and have results, photos, and videos to show for it. Their generosity and patience are very much appreciated.

Proper expedition clothing and equipment is expensive. If you cut corners on price and quality, you risk being dangerously ill equipped, so having a sponsor who both advises what you might need and provides it is invaluable.

In the Wakhan Corridor, the greatest challenge from a clothing and equipment perspective is the range of temperatures: in August, we had scorching hot days and sub-zero nights, where ice formed on the fly sheets of the tents. Being able to add on and remove multiple layers is essential, as is having equipment with good thermal properties and which will also keep out the wind.

Sophie’s favourite item: The item I wore most is my Pacific Green JWP t-shirt with 3/4 length sleeves. It’s an ideal base layer earlier in the morning, with a fleece and jacket on top; but once the days warmed up, I could strip everything else off and still have enough protection (at least on my body and arms!) from the intense sun. The cut, neckline, and sleeve length was also modest enough that I didn’t worry about disapproving looks. The fabric is light, doesn’t crease, and doesn’t really to show the dirt or sweat, so this short was my go-to, day in, day out.

Kamila’s favourite item: Our tent! It was my first time camping and I was afraid of how uncomfortable and unsafe it will be, but on the contrary! Incredibly warm, safe, nearly sound proof and cozy. The views from our tent were incredible, I loved waking up early in the morning to the sun or at night to see the stars, yet the tent would keep its warmth.

When we first planned the Oxus Expedition in 2020/21, we expected to enter Afghanistan at Ishkashim, the border town split between Tajikistan and Afghanistan, which is the gateway to the Wakhan Corridor. This is where I [Sophie] had crossed the border on three previous trips, and although the bridge / border was closed due to COVID restrictions, I expected that to be a temporary situation and one which could be resolved, if need be, with special permission from Dushanbe

Five years on, COVID is little more than a memory but the Ishkashim border hasn’t reopened, a sign of the uneasy diplomatic relationship between the two countries. You can cross further west at Sher Khan Bandar, but for us it was more convenient to go straight from Uzbekistan to Afghanistan, saving the need for yet another Tajik visa.

Road travel within Afghanistan is much easier and safer than it was under the previous Afghan government. The Taliban proudly advertise the improved security situation, even though one major reason for it is that they themselves are no longer planting roadside bombs or kidnapping foreigners for ransom. We could therefore drive — without a convoy or armed escort — from the Hairatan border crossing to Mazar-i Sharif, then via Kunduz to Faizabad and Ishkashim. That part of the journey, on reasonable roads, would take two days.

Once in the Wakhan Corridor, we continued east, still by car but at a much slower pace. The roads in the valley, though extended and improved in recent years, are still little more than dirt tracks, with frequent river crossings and other obstacles. As the altitude increases significantly, it is also necessary to acclimatise, so we stopped a night in the guesthouses in Qala-e Panja and in Sarhad-e Broghil. The new road from Sarhad to Bozai Gumbaz is hair raising, and although I had full trust in our driver, Abdurahmon, I could not say the same for the car, which rattled, squeaked, and generally complained, especially on precarious downhill stretches when the brakes were applied.

In the Little Pamir, overlooking Lake Chaqmaqtin, I finally felt that the Oxus Expedition might actually conclude this year. The late, turquoise and idyllic, with peaks and glaciers either side, has often been described as the source of the Oxus, though that was one thing we were out to disprove.

There is now a road along the northern shore of Chaqmaqtin to Tajikistan, and another through the Wakhjir Valley to China, though the latter hasn’t yet opened the border crossing. Where we were going — the Chelab Valley — there was still no road, so we left the 4×4 in the Kyrgyz winter settlement at the valley’s mouth and transferred our baggage to two horses and a donkey. Mahmud Omar and Ahmad, two young Kyrgyz men, joined us for the next four days to care for them. Bags packed, we set off on foot to establish a base camp half way along the valley, around four hours’ walk from the vehicle.

In 2021, the Oxus Expedition was postponed because of the collapse of the Afghan government and the Taliban’s return to power. In 2024, security had improved and the expedition’s prospects looked promising, but just days before we were due to arrive in Afghanistan, the Taliban banned foreigners from entering the Wakhan Corridor. It was therefore with a weary caution that in spring 2025 we once again began planning a trip — by this stage the last remaining part of the expedition route. We booked flights, we made our ground arrangements with the very patient Azim Ziyahee from Wakhan Adventure, we updated our travel insurance, and we trained.

By August 2025, it was possible to cross the Friendship Bridge in Termez, Uzbekistan, and enter Afghanistan near Mazar-i Sharif. For a variety of reasons, this was a more attractive option than transiting through Tajikistan, as we had planned in previous years. We arrived in Termez on a hot Thursday afternoon on the flight from Tashkent and checked into the gorgeous Comfortable Homestay, planning to get our visas the following morning.

Afghanistan’s consulate in Termez is on the lower floor of a new residential building. The red, black, and green flag of Afghanistan hangs on roadside of the building, but in the courtyard the white Taliban flag is flying. It was a reminder of the diplomatic complexities of engaging with a state whose government is not formally recognised.

The challenge? The consulate was shut. The website said it was open, and a tourist we met at the homestay had successfully applied for her visa the day before. We googled “public holidays in Afghanistan” but nothing showed up. The security guard was adamant, however: no one is here; come back on Monday. Friday 15 August was, we would subsequently learn, Victory Day, the fourth anniversary of the Taliban’s return to power.

Our plans were upended, though not irreparably. Our arrival in Afghanistan would be delayed (yet again), but this time only for a few days. We would enter, bureaucracy permitting, on Monday evening instead of Saturday. In the meantime, there was nothing for it but sightseeing in Termez and drinking a few last-minute beers in the garden at Diplomat restaurant.

Assalomu alaykum!

My name is Kamila and, to be completely honest, I had no interest in travelling to Afghanistan at first—not until about four years ago. It all began with my discovery of lapis lazuli: its history, its connection to the British monarchy, and the regions from which it originates. The much-admired royal blue of the British Crown, in fact, was possibly derived from the deep hue of lapis lazuli.

As I started gathering information, I found myself increasingly drawn to Badakhshan and the Pamirs, and gradually began learning about the Wakhan Corridor. The rich history of the region resonated with me on a personal level, linking back to my own roots in neighbouring Uzbekistan. Take Balkh, for example—often regarded as the twin city of Samarkand. Even Kabuli Palau rivals Uzbek plov (yes, I dare say it might even be better!).

And the people? Among the warmest I have ever encountered, even here in London. The blend of cultures, ethnicities, and languages feels so close to home. I hope to learn more about the communities of the Wakhan Corridor, for my greatest curiosity always lies with people—their stories, their resilience, and their everyday lives.

Though I am new to camping, I am no stranger to hiking mountains, valleys, and steep hills. After all, I am a daughter of the Fergana Valley, and I cannot wait to witness with my own eyes the beauty I have so often read about in my searches.